by Claudia Segre

THE BLOGGER’S CORNER. The question is not whether artificial intelligence will change work, but who is seizing the opportunity of this transformation and who will be left behind. Europe seems increasingly determined to play its part.

17 February 2026

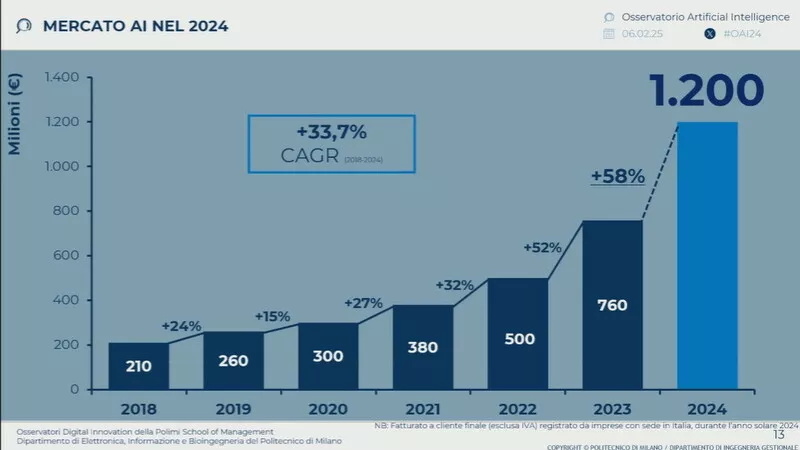

From the World Economic Forum in Davos to the Consumer Electronics Show in Los Angeles, to the Cannes AI Festival, today, among the main events dedicated to artificial intelligence, the message that emerges is unequivocal: AI is no longer a promise, but a concrete structural reality. Artificial intelligence is already a fully integrated part of global production processes. And, like any infrastructure, it does not just improve what already exists: it redraws the balance of power, redefines the skills required, and opens up new economic and social opportunities.

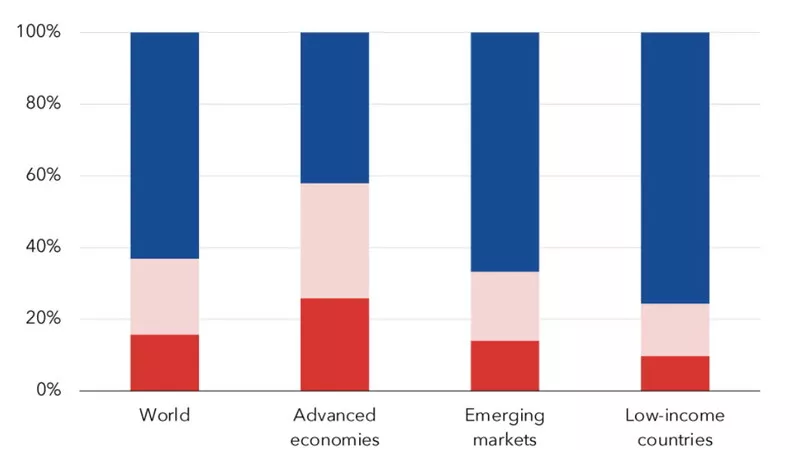

Kristalina Georgieva, Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), spoke of a “tsunami” on labour and, citing the IMF’s clear estimates, stated that up to 60% of jobs in advanced economies and around 40% globally will be transformed by AI in the coming years. This is not just a matter of replacement, but of a profound hybridisation of tasks, involving the use of technical and cross-cutting skills. Cognitive professions – finance, consulting, marketing, and IT – are no longer “safe”: they will obviously be redefined. And if the trauma left by COVID on the younger generations was not enough, here is another tough test that fuels uncertainty and burnout. And the signs are already visible. Recent studies from Stanford show that, in the sectors most exposed to generative AI – software development, customer service – workers between the ages of 22 and 25 have seen their probability of employment reduced by up to 13%.

Anthropic’s latest venture, with billion-dollar valuations and strategic partnerships in the cloud sector and foundation models, tells another truth: AI is concentrating value at the heart of the software ecosystem. Companies are redesigning their job descriptions, integrating the need for AI skills into all functions. It is no longer just a matter of developers, but of widespread, true “AI literacy”, which translates into the ability to supervise, interpret, and govern intelligent systems by adequately trained human resources.

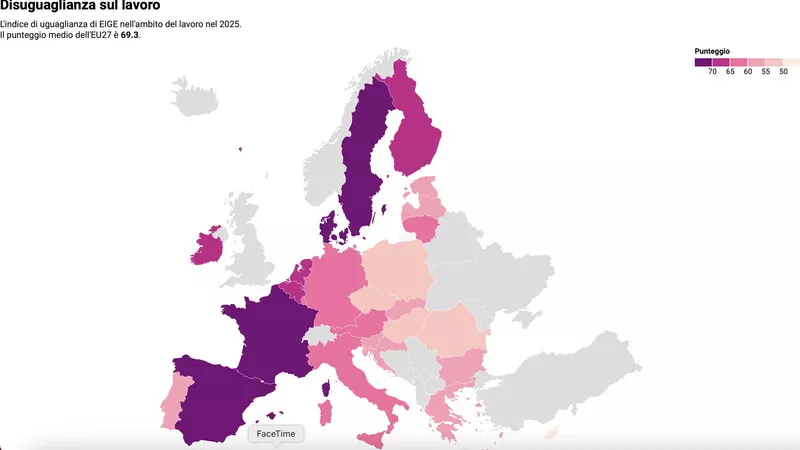

The labour market is not facing a simple phase of automation typical of phase 3.0 of the industrial revolution, but a structural transformation that is relentlessly affecting the field of skills. The worker of the future will not be replaced by AI: they will be evaluated on their ability to use it. This is where the ILO, the International Labour Organisation, comes in with its recent report “Employment and social trends”: AI has an asymmetrical impact: young people, low-skilled workers, and women in administrative and support roles are more exposed to the replacement of routine tasks. Meanwhile, according to the EIGE’s Gender Equality Index 2025, the EU appears to have achieved a score of 69.3 out of 100 in the field of work, with persistent segregation of women: only 20% of ICT specialists are women, while 35% of managers are women. In STEM degrees, women account for about one-third of graduates. If AI becomes the engine of growth, but women remain underrepresented in STEM and technology roles, the risk is clear: a new digital gender divide, in which everyone has something to lose.

Therefore, defining AI as a single tsunami is misleading if we do not first talk about governance. It is certainly not technology that creates inequality: it is the absence of adequate labour policies. To ride these changes, we need continuous, targeted, and accessible training from primary school onwards, active labour policies to accompany the transition, and awareness of an epoch-making change.

But a third lever is also needed, one that is too often considered marginal: gender mainstreaming in AI. It is not enough to “include” women; we need to design artificial intelligence systems that do not replicate certain biases, support girls’ access to STEM subjects, encourage female leadership in tech companies, and promote visible and authentic role models.

AI is the new infrastructure of work, and gender equality is a crucial condition for competitiveness. It is not a separate ethical issue: it is a primary factor in economic resilience.

The A&T 2026 Turin trade fair is coming to a close, and AI is still emerging as a powerful operational lever for industrial competitiveness, including for SMEs. In a global market marked by tensions and international competition, digitalisation and intelligent systems are becoming conditions for survival. Collaborative robots, or cobots, already account for 12% of global sales and are growing. New technologies could create 1.8 million jobs, while in Italy, 9 million workers will need to retrain.

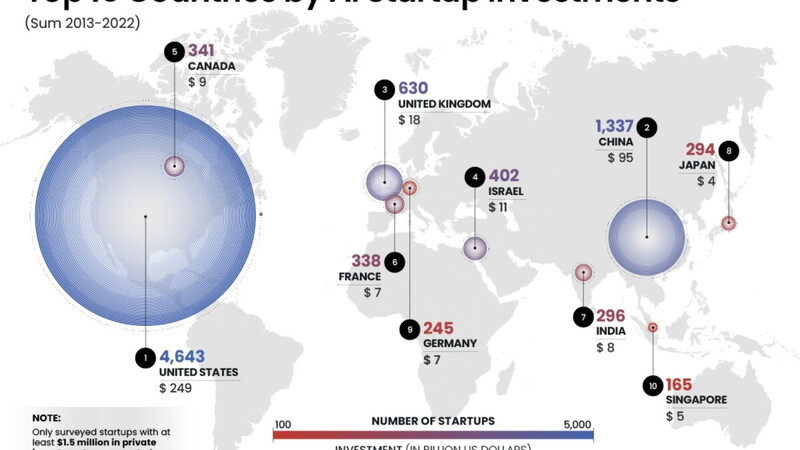

From Davos to Los Angeles, from Cannes to Turin: the future of work is already here. And there is an urgent need to direct investment towards AI in Europe, including through common debt. This was a much-discussed topic at the recent EU summit in Belgium: France, at the forefront, has allocated the largest investment package in the EU after the UK, with €109 billion, and it is no coincidence that the most important AI start-up in terms of capitalisation in the EU is French, Mistral AI.

The question is therefore not whether AI will change work. The question is: who is seizing the opportunity of this transformation and who will be left behind? Europe seems increasingly determined finally to do its part, thanks in part to Draghi’s words of encouragement, and hopefully it will have the courage and foresight to strive to reduce the gap with the United States with the spirit necessary to start afresh, leaving behind too much hesitation, which is all too human and borders on self-harm!